Tagged: Susanne Jaeggi

Beware a fast track to “better brains”

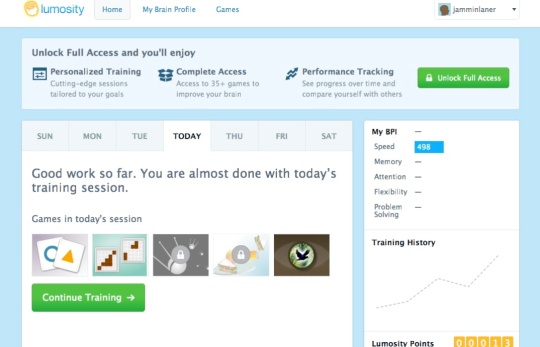

A personalized home page on Lumosity, one of the growing number of companies that offer online brain training.

It’s an alluring promise: play some games and get smarter. That’s the idea behind brain training, which has piggybacked off neuroscience to become its own little commercial field. Groups like LearningRx and Lumosity — you may have seen ads for the latter — offer regimes of online games meant to improve aspects of cognition like memory, attention and speed.

Brain training was the subject of last week’s CNS Public Talk, given by University of Maryland professor and working memory researcher Susanne Jaeggi. Jaeggi became a media go-to on the topic after publishing a paper in 2008 suggesting that memory training can boost general intelligence, that hard-to-pin-down quality long associated with IQ scores. Unfortunately, I missed Jaeggi’s lecture. But I’ve been prompted by her appearance at Penn to look into brain training from both the academic and commercial sides. What I’ve begun to find is that the two sides sometimes get way too blurred, an outcome not all that surprising for a topic with so much popular appeal.

Brain training’s made waves in the press, and it’s not hard to see why. Most people I know, myself included, experience internal wars between our aspirational and lazy impulses. We like to get better at things, but what we really love is to see results after putting in the least work possible. On its surface, brain training answers both desires: it’s packaged as a way we can make ourselves smarter in half-hour long chunks a few times a week. It’s a time commitment that amounts to keeping up with a couple new TV shows, and an experience that amounts to playing basic computer games.

Slap the “neuroscience-supported” label on there and you’ve got a gold mine: a new approach to self-help, legitimized by the oft-misunderstood authority that is “science.”

OK, at this point I might be sounding too cynical. Yes, my inner curmudgeon balks at the idea of intelligence or smarts being stripped down to technical terms like “working memory,” at the neglect of traits like creativity and depth of thought. But on a basic level, I’m all for tools that can make lives better. It’d be great if brain training could genuinely help individuals with cognitive problems, young students, or really just anyone improve at everyday facets of thinking like juggling many pieces of information. Better still if these improvements translate to other aspects of thinking — say, problem solving and communicating — that may reflect broader intelligence.

And beyond the potential benefits, there is reason to at least study brain training in relation to neuroplasticity, or the brain’s capacity to change. After all, some nosing through the work of training supporters like Jaeggi shows that the relevant research doesn’t come from hacks.

My thing is, though, the most encouraging (if still controversial) work here has been behavioral. When it comes to endorsing these specific training methods, the support from neuroscience is largely indirect or speculative. So as I explore my trial Lumosity account — where I can’t do much, since I won’t pay — it’s hard not to sigh when the site references “neurogenesis” to explain how these games will better my brain.

Isn’t it enough to tell me that if I keep playing the offered memory games, I might stop leaving my keys everywhere? Do these sites have to make dubious claims like they’re literally spurring the growth of new neurons in my brain? A more academic perspective says no: the most recent training-related paper on Jaeggi’s site concludes that more research is needed to say anything about how working memory training actually affects the brain.

So maybe the claims on sites like Lumosity should change. Brain training’s not so much “neuroscience-approved” — it’s got some behavioral support that’s still being interpreted. Any support from neuroscience is very much under construction.